We lost the Battle of Bladensburg to a small British force of just over four thousand. A few hours later those British marched unopposed into Washington and began to burn the government buildings. Flames from the burning Capitol and Presidential Mansion lit the night sky and were visible from Baltimore, 35 miles away.

I wanted Dolley’s perception of this battle to be as close to what really happened as I could make it. Not easy, since none of the historic accounts align perfectly. Rita Mae Brown described the battle very well in her excellent book Dolley — A Novel of Dolley Madison in Love and War (see Bibliography), certainly better than my first attempt . . . but it was from an omniscient point of view, and I wanted it to be from Ranger-trained Dolley’s point of view. So I discarded my analytical scribblings and dug into more detailed, more contemporary sources and maps.

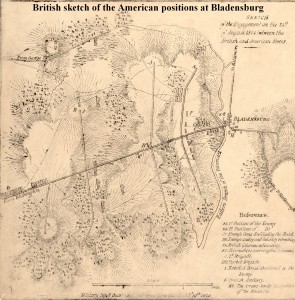

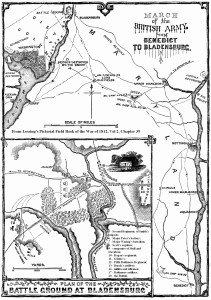

Maps.

Since Bladensburg is currently full of houses and businesses (walking tour of Bladensburg), I used maps from that period that portrayed the terrain and units. Some of these are better than others. For example, the British map shows General Stansbury’s Brigade as our second line of defense positioned where they observed it: a quarter mile behind Major Pinkney’s Rifles. General Winder intended that Brigade to be the first line of defense, originally a hundred yards behind Pinkney: Secretary of State Monroe moved it without consulting General Winder (the overall commander) or General Stansbury.

Events.

To piece together what Dolley saw as she viewed the battle I studied several ancient & detailed sources, then diced them up and put them into chronological order. I didn’t use everything, just the parts I deemed useful.

Mahan = Sea Power In Its Relations To The War Of 1812 By Captain A.T. Mahan. Download.

Lossing = Pictorial Field-Book Of The War Of 1812. By Benson J. Lossing 1869, Ch 39. Read Online

Gleig = The Campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans, 1814-1815 by Rev. G. R. Gleig, M.A., Chaplain-General. Download.

Before 24 August 1814

Mahan – Secretary of War thought he could assemble one thousand regulars, independent of artillerists in the forts.[2] The Secretary of the Navy could furnish one hundred and twenty marines, and the crews of Barney’s flotilla, estimated at five hundred.[2] For the rest, dependence must be upon militia, a call for which was issued to the number of ninety-three thousand, five hundred. [370] Of these, fifteen thousand were assigned to Winder, as follows: From Virginia, two thousand; from Maryland, six thousand; from Pennsylvania, five thousand; from the District of Columbia, two thousand. [371] So ineffective were the administrative measures for bringing out this paper force of citizen soldiery, the efficiency of which the leaders of the party in power had been accustomed to vaunt, that Winder, after falling back from point to point before the enemy’s advance, because only so might time be gained to get together the lagging contingents, could muster in the open ground at Bladensburg, five miles from the capital, where at last he made his stand, only the paltry five or six thousand stated by the court.

Lossing – Now let us see what forces were at the disposal of General Winder for the defense of Washington. There were two small brigades of District troops. One of these comprised the militia and volunteers of Washington and Georgetown, arranged in two regiments under Colonels Magruder and Brent, and was commanded by General Walter Smith, of Georgetown. Attached to the brigade were two companies of light artillery, commanded respectively by Major George Peter, of the regular army, and Captain Benjamin Burch, a soldier of the Revolution. There were also two rifle companies under Captains Doughty and Stull. This brigade numbered, on the morning of the 21st of August, one thousand and seventy men. The second brigade was commanded by General Robert Young, and numbered five hundred men. It comprised a company of artillery led by Captain Marsteller. It was chiefly employed in defending the approaches to Fort Washington, about twelve miles below the capital.

Brigadier General West, of Prince George’s County, had troops on the look-out toward the Potomac.

The troops from Baltimore comprised a greater portion of the brigade of General Stansbury, formed in two regiments under Lieutenant Colonels Ragan and Schutz, thirteen hundred and fifty in number; and the Fifth Regiment, under Colonel Sterett, with artillery and riflemen already mentioned, the latter under the celebrated William Pinkney. The whole force from Baltimore was about two thousand two hundred, commanded by General Stansbury as chief.

Besides these there were various detachments of Maryland militia, under the respective command of Colonels W. D. Beall (of the Revolution) and Hood, Lieutenant Colonel Kramer, and Majors Waring and Maynard – in all less than twelve hundred. There was also a regiment of Virginia militia under Colonel George Minor, six hundred strong, with one hundred cavalry.

The regular army contributed three hundred men from the Twelfth, Thirty-sixth, and Thirty-eighth Regiments, under Lieutenant Colonel William Scott. To these must be added the sailors of Barney’s flotilla, four hundred, and one hundred and twenty marines from the navy yard at Washington, furnished with two 18-pounders and three 12-pounders.

There were also various small companies of volunteer cavalry from the District, Maryland, and Virginia, under Lieutenant Colonel Tilghman, and Majors O. H. Williams and Charles Sterett, three hundred in number, and a squadron of United States dragoons commanded by Major Laval. The whole force was about seven thousand strong, of whom nine hundred were enlisted men. The cavalry did not exceed four hundred in number. The little army had twenty-six pieces of cannon, of which twenty were only 6-pounders. This force, if concentrated, would have been competent to roll back the invasion had the commanding officer been untrammeled by the interference of the President and his Cabinet.

Mahan – Barney had abandoned the boats on the 21st, leaving with each a halfdozen of her crew to destroy her at the last moment. This was done when the British next day approached; one only escaping the flames.

Lossing – 22 August letter from Monroe to Madison:

“The enemy are advanced six miles on the road to the Wood Yard, and our troops are retiring. Our troops were on the march to meet them, but in too small a body to engage. General Winder proposes to retire till he can collect them in a body. The enemy are in full march to Washington. Have the materials prepared to destroy the bridges. J. MONROE. “P.S. – You had better remove the records.”

This message produced the wildest excitement in the national capital, then a straggling town of between eight and nine thousand inhabitants, and caused a sudden and confused exodus of all the timid and helpless ones who were able to leave.

Lossing – [Soldiers] were undisciplined and untried, and surrounded and influenced by a crowd of excited civilians, to whose “officious but well-intended information and advice” the general was compelled to listen. In addition to this intrusion and interference of common men, he was embarrassed by the presence and suggestions of the President and his Cabinet ministers, the most of them utterly ignorant of military affairs.

Lossing – 23 August morning: The fatigued little army at Long Old Fields had reposed but a short time when, at two o’clock in the morning (August 23), a timid sentinel gave a false alarm, and they were summoned to their feet in battle order. They were soon dismissed, and slept on their arms until dawn. At sunrise they were ordered to strike their tents, load the baggage wagons, and have every thing in readiness to move within an hour. When every thing was prepared for marching they were reviewed by President Madison.

Mahan – From Upper Marlborough, where the British had arrived, two roads led to Washington. One of these, the left going from Marlborough, crossed the Eastern Branch near its mouth; the other, less direct, passed through Bladensburg. Winder expected the British to advance by the former; and upon it Barney with the four hundred seamen remaining to him joined the army, at a place called Oldfields, seven miles from the capital. This route was militarily the more important, because from it branches were thrown off to the Potomac, up which the frigate squadron under Captain Gordon was proceeding, and had already passed the Kettle-bottoms, the most difficult bit of navigation in its path. The side roads would enable the invaders to reach and co-operate with this naval division; unless indeed Winder could make head against them. This he was not able to do; but he remained almost to the last moment in perplexing uncertainty whether they would strike for the capital, or for its principal defence on the Potomac, Fort Washington, ten miles lower down. [373]

Mahan – the British advanced, as anticipated, by the left-hand road, and at nightfall of August 23 were encamped about three miles from the Americans.

Mahan – Winder feared to await the enemy, because of the disorder to which his inexperienced troops would be exposed by a night attack, causing possibly the loss of his artillery; the one arm in which he felt himself superior. He retired therefore during the night by the direct road, burning its bridge. This left open the way to Bladensburg, which the British next day followed…

Lossing – The night of the 23d of August was marked by great excitement in the National capital. The President and his Cabinet indulged in no slumbers, for Ross, the invader, was bivouacked at Melwood, near the Long Old Fields, about ten miles from the city, and Winder’s troops, worn down and dispirited, were fugitives before him. Laval’s horsemen were exhausted, and Stansbury’s troops at Bladensburg were too wearied with long marching to do much fighting without some repose.

Gleig – 24 August – We had now proceeded about nine miles, during the last four of which the sun’s rays had beat continually upon us, and we had inhaled almost as great a quantity of dust as of air. Numbers of men had already fallen to the rear, and many more could with difficulty keep up; consequently, if we pushed on much farther without resting, the chances were that at least one half of the army would be left behind.

Lossing – 24 August – Winder’s head-quarters were at Combs’s, near the Eastern Branch Bridge, and at dawn the President and several of his Cabinet ministers were there. 25 Before their arrival, General Winder (who was greatly fatigued in body and mind, and had received a severe injury from a fall during the night) had sent a note to the Secretary of War, expressing a desire to have the counsel of that officer and of the government.

Lossing – While Winder and the government were in council, Ross moved toward Bladensburg. Laval’s scouts first brought intelligence of the fact to head-quarters. They were soon followed by an express from Stansbury, giving positive information that the British were marching in that direction, with the view, no doubt, of crushing the little force of Baltimoreans near the Bladensburg Mill.

Mahan – 24 August – On the morning of the battle the Secretary of War rode out to the field, with his colleagues in the Administration, and in reply to a question from the President said he had no suggestions to offer; “as it was between regulars and militia, the latter would be beaten.” [372] The phrase was Winder’s absolution; pronounced for the future, as for the past. The responsibility for there being no regulars did not rest with him, nor yet with the Secretary, but with the men who for a dozen years had sapped the military preparation of the nation.

Lossing – 24 August – …it was ten o’clock in the morning when Winder ordered General W. Smith, with the whole of his troops, to hasten toward Bladensburg. Barney was soon afterward ordered to move with his five hundred men, and the Secretary of State, who had seen some military service in the Revolution, was requested by the President and General Winder to hasten to Stansbury and assist him in properly posting his troops. Mr. Monroe was immediately followed by General Winder and his staff. The Secretary of War then followed; and lastly the President and Attorney General, accompanied by some friends, all on horseback, rode on toward the expected theatre of battle. 27 Stansbury seems not to have been well pleased with the aid of the Secretary of State, for he afterward intimated that “somebody,” without consulting him, changed and deranged his order of battle. That “somebody” was Colonel Monroe….

Mahan – [British ] arriving at the village [Bladensburg] towards noon of the 24th.

Gleig – The hour of noon was approaching, when a heavy cloud of dust, apparently not more than two or three miles distant, attracted our attention…. for on turning a sudden angle in the road, and passing a small plantation, which obstructed the vision towards the left, the British and American armies became visible to one another. … Across [east branch] was thrown a narrow bridge, extending from the chief street in that town to the continuation of the road, which passed through the very centre of their position; and its right bank (the bank above which they were drawn up) was covered with a narrow stripe of willows and larch [pine] trees, whilst the left was altogether bare, low, and exposed.

Mahan – Contrary to Winder’s instruction, the officer stationed there had withdrawn his troops across the stream, abandoning the place, and forming his line on the crest of some hills on the west bank.

Troop Deployment

Mahan – The impression which this position made upon the enemy was described by General Ross, as follows: “They were strongly posted on very commanding heights, formed in two lines, the advance occupying a fortified house, which with artillery covered the bridge over the Eastern Branch, across which the British troops had to pass. A broad and straight road, leading from the bridge to Washington, ran through the enemy’s position, which was carefully defended by artillerymen and riflemen.” [374]

Mahan – The American line had been formed before Winder came on the ground. It extended across the Washington road as described by Ross. A battery on the hill-top commanded the bridge, and was supported by a line of infantry on either side, with a second line in the rear. Fearing, however, that the enemy might cross the stream higher up, where it was fordable in many places, a regiment from the second line was reluctantly ordered forward to extend the left; and Winder, when he arrived, while approving this disposition, carried thither also some of the artillery which he had brought with him. [375]

Lossing – In the triangular field formed by the two roads just mentioned, and near the mill, General Stansbury’s command was posted on the morning of the 24th. On the brow of a little eminence in that field, three hundred and fifty yards from the Bladensburg Bridge, between a large barn 29 and the Washington Road, a barbette earth-work had been thrown up for the use of heavy cannon. Behind this work were the artillery companies from Baltimore, under Captains Myers and Magruder, one hundred and fifty strong, with six 6-pounders. These were too small for the high embankment, and embrasures were cut so that they might command the bridge and both roads. Major Pinkney’s riflemen were on the right of the battery, near the junction of the roads, and concealed by the shrubbery on the low ground near the river. Two companies of militia, under Captains Ducker and Gorsuch, acting as riflemen, were stationed in the rear of the left of the battery, near the barn and the Georgetown Road. About fifty yards in the rear of Pinkney’s riflemen was Sterett’s Fifth Regiment of Baltimore Volunteers, while the regiments of Ragan and Schutz were drawn up en echelon, 30 their right resting on the left of Ducker’s and Gorsuch’s companies, and commanding the Georgetown Road. The cavalry, about three hundred and eighty in all, were placed somewhat in the rear, on the extreme left, and seem not to have taken any part in the battle that ensued.

Lossing – Colonel Monroe, without consulting General Stansbury, and in face of the enemy, then on the other side of the Eastern Branch, proceeded to change it, by moving the Baltimore regiments of Sterett, Ragan, and Schutz a quarter of a mile in the rear of the artillery and riflemen, their right resting on the Washington Road. This formed a second line in full view of the enemy, within reach of his Congreve rockets, entirely uncovered, and so far from the first line as not to be able to give it immediate support in case of an attack This was a blunder that proved disastrous, but it was made too late to be corrected, the enemy was so near.

Lossing – General Winder in the mean time had arrived on the field, and posted a third and rear line on the crown of the hills, near the residence of the late John C. Rives, proprietor of the Washington Globe, about a mile from the Bladensburg Bridge. This line embraced a regiment of Maryland militia, under Colonel Beall, which had just arrived from Annapolis, and was posted on the extreme right; Barney’s flotilla-men, who formed the centre on the Washington Road, with two 18 pounders planted in the highway a few yards from the site of Rives’s barn, a portion of the seamen acting as artillerists; and Colonel Magruder’s District militia, regulars under Lieutenant Colonel Scott, and Peter’s battery, who formed the left.

Lossing – About five hundred yards in front of this position the road descends into a gentle ravine, which was then, as now, crossed by a small bridge (Tournecliffe’s), on the north of which it widens into a little grassy level, and formed the dueling-ground where Decatur and others lost their lives.

Lossing – Overlooking it, about one hundred and fifty yards from the road, is an abrupt bluff on which the companies of Captains Stull and Davidson were posted in position to command that highway. Lieutenant Colonel Scott, with his regulars, Colonel Brent, with the Second Regiment of General Smith’s brigade, and Major Waring, with the battalion of Maryland militia, were posted in the rear of Major Peter’s battery. Magruder was immediately on the left of Barney’s men, his right resting on the Washington Road; and Colonel Kramer, with a small detachment, was thrown forward of Colonel Beall.

Gleig – I have said that the right bank of the Potomac was covered with a narrow stripe of willow and larch trees. Here the Americans had stationed strong bodies of riflemen, who, in skirmishing order, covered the whole front of their army. Behind this plantation, again, the fields were open and clear, intersected, at certain distances, by rows of high and strong palings. About the middle of the ascent, and in the rear of one of these rows, stood the first line, composed entirely of infantry; at a proper interval from this, and in a similar situation, stood the second line; while the third, or reserve, was posted within the skirts of a wood, which crowned the heights. The artillery, again, of which they had twenty pieces in the field, was thus arranged on the high road, and commanding the bridge, stood two heavy guns; and four more, two on each side of the road, swept partly in the same direction, and partly down the whole of the slope into the streets of Bladensburg. The rest were scattered, with no great judgment, along the second line of infantry, occupying different spaces between the right of one regiment and the left of another; whilst the cavalry showed itself in one mass, within a stubble field, near the extreme left of the position. Such was the nature of the ground which they occupied, and the formidable posture in which they waited our approach; amounting, by their own account, to nine thousand men, a number exactly doubling that of the force which was to attack them.

Battle

Lossing – at noon, the enemy were seen descending the hills beyond Bladensburg, and pressing on toward the bridge.

Gleig – In the mean time, our column continued to advance in the same order which it had hitherto preserved. The road, having conducted us for about two miles in a direction parallel with the river, and of consequence with the enemy’s line, suddenly turned, and led directly towards the town of Bladensburg. Being of course ignorant whether this town might not be filled with American troops, the main body paused here till the advanced guard should reconnoitre. The result proved that no opposition was intended in that quarter, and that the whole of the enemy’s army had been withdrawn to the opposite side of the stream, whereupon the column was again put in motion, and in a short time arrived in the streets of Bladensburg, and within range of the American artillery.

Lossing – At half past twelve they were in the town, and came within range of the heavy guns of the first American line.

Gleig – Immediately on our reaching this point, several of their guns opened upon us, and kept up a quick and well-directed cannonade, from which, as we were again commanded to halt, the men were directed to shelter themselves as much as possible behind the houses. The object of this halt, it was conjectured, was to give the General an opportunity of examining the American line, and of trying the depth of the river; because at present there appeared to be but one practicable mode of attack, by crossing the bridge, and taking the enemy directly in front. To do so, however, exposed as the bridge was, must be attended with bloody consequences, nor could the delay of a few minutes produce any mischief which the discovery of a ford would not amply compensate. But in this conjecture we were altogether mistaken; for without allowing time to the column to close its ranks, or to be joined by such of the many stragglers as were now hurrying, as fast as weariness would permit, to regain their places, the order to halt was countermanded, and the word given to attack; and we immediately pushed on at double quick time, towards the head of the bridge.

Mahan – The anxiety of the Americans was therefore for their left. The British commander was eager to be done with his job, and to get back to his ships from a position militarily insecure. He had long been fighting Napoleon’s troops in the Spanish peninsula, and was not yet fully imbued with Drummond’s conviction that with American militia liberties might be taken beyond the limit of ordinary military precaution. No time was spent looking for a ford, but the troops dashed straight for the bridge. The fire of the American artillery was excellent, and mowed down the head of the column; but the seasoned men persisted and forced their way across. At this moment Barney was coming up with his seamen, and at Winder’s request brought his guns into line across the Washington road, facing the bridge.

Lossing –The British commenced hurling rockets at the exposed Americans, and attempted to throw a heavy force across the bridge, but were driven back by their antagonists’ cannon, and forced to take shelter in the village and behind Lowndes’s Hill, in the rear of it. 33

Lossing –Again, after due preparation, they advanced in double-quick time; and, when the bridge was crowded with them, the artillery of Winder’s first and second lines opened upon them with terrible effect, sweeping down a whole company. The concealed riflemen, under Pinkney, also poured deadly volleys into their exposed ranks; but the British, continually re-enforced, pushed gallantly forward, some over the bridge, and some fording the stream above it, and fell so heavily upon the first and unsupported line of the Americans that it was compelled to fall back upon the second.

Gleig – When once there, however, everything else appeared easy. Wheeling off to the right and left of the road, they dashed into the thicket, and quickly cleared it of the American skirmishers; who, falling back with precipitation upon the first line, threw it into disorder before it had fired a shot. The consequence was, that our troops had scarcely shown themselves when the whole of that line gave way, and fled in the greatest confusion, leaving the two guns upon the road in possession of the victors.

Lossing –A company, whose commander is unnamed in the reports of the battle, were so panic-stricken that they fled after the first fire, leaving their guns to fall into the hands of the enemy.

Lossing –The first British brigade were now over the stream, and, elated by their success, did not wait for the second. They threw away their knapsacks and haversacks, and pushed up the hill to attack the American second line in the face of an annoying fire from Captain Burch’s artillery.

Gleig – But here it must be confessed that the light brigade was guilty of imprudence. Instead of pausing till the rest of the army came up, the soldiers lightened themselves by throwing away their knapsacks and haversacks; and extending their ranks so as to show an equal front with the enemy, pushed on to the attack of the second line. The Americans, however, saw their weakness, and stood firm, and having the whole of their artillery, with the exception of the pieces captured on the road, and the greater part of their infantry in this line, they first checked the ardour of the assailants by a heavy fire, and then, in their turn, advanced to recover the ground which was lost.

Lossing –They weakened their force by stretching out so as to form a front equal to that of their antagonists. It was a blunder which Winder quickly perceived and took advantage of. He was then at the head of Sterett’s regiment. With this and some of Stansbury’s militia, who behaved gallantly, he not only checked the enemy’s advance, but, at the point of the bayonet, pressed their attenuated line so strongly that it fell back to the thickets on the brink of the river, near the bridge,

Lossing – [Brits] maintained its position most obstinately until re-enforced by the second brigade. Thus strengthened, it again pressed forward, and soon turned the left flank of the Americans, and at the same time sent a flight of hissing rockets over and very near the centre and right of Stansbury’s line.

Gleig – In this state the action continued till the second brigade had likewise crossed, and formed upon the right bank of the river; when the 44th regiment moving to the right, and driving in the skirmishers, debouched upon the left flank of the Americans, and completely turned it. In that quarter, therefore, the battle was won; because the raw militia-men, who were stationed there as being the least assailable point, when once broken could not be rallied. But on their right the enemy still kept their ground with much resolution; nor was it till the arrival of the 4th regiment, and the advance of the British forces in firm array to the charge, that they began to waver. Then, indeed, seeing their left in full flight, and the 44th getting in their rear, they lost all order, and dispersed, leaving clouds of riflemen to cover their retreat; and hastened to conceal themselves in the woods, where it would have been madness to follow them.

Mahan – Soon after this, a few rockets passing close over the heads of the battalions supporting the batteries on the left started them running, much as a mule train may be stampeded by a night alarm. It was impossible to rally them. A part held for a short time; but when Winder attempted to retire them a little way, from a fire which had begun to annoy them, they also broke and fled. [376]

Lossing –The frightened regiments of Schutz and Ragan broke, and fled in the wildest confusion.

Lossing –Winder tried to rally them, but in vain. Sterett’s corps maintained their ground gallantly until the enemy had gained both their flanks, when Winder ordered them and the supporting artillery to retire up the hill. They, too, became alarmed, and the retreat, covered by riflemen, was soon a disorderly flight.

Gleig – The rout was now general throughout the line. The reserve, which ought to have supported the main body, fled as soon as those in its front began to give way; and the cavalry, instead of charging the British troops, now scattered in pursuit, turned their horses’ heads and galloped off, leaving them in undisputed possession of the field, and of ten out of the twenty pieces of artillery.

Lossing –The first and second line of the Americans having been dispersed, the British, flushed with success, pushed forward to attack the third. Peter’s artillery annoyed, but did not check them; and the left, under the gallant Colonel Thornton, soon confronted Barney, in the centre, who maintained his position like a genuine hero, as he was. His 18-pounders enfiladed the Washington Road, and with them he swept the highway with such terrible effect that the enemy filed off into a field, and attempted to turn Barney’s right flank. There they were met by three 12-pounders and marines, under Captains Miller and Sevier, and were badly cut up. They were driven back to the ravine already mentioned as the dueling-ground, leaving several of their wounded officers in the hands of the Americans. Colonel Thornton, who bravely led the attacking column, was severely wounded, and General Ross had his horse shot under him.

Lossing –The flight of Stansbury’s troops left Barney unsupported in that direction, while a heavy column was hurled against Beall and his militia, on the right, with such force as to disperse them. The British light troops soon gained position on each flank, and Barney himself was severely wounded. When it became evident that Minor’s Virginia troops could not arrive in time to aid the gallant flotilla-men, who were obstinately maintaining their position against fearful odds, and that farther resistance would, be useless, Winder ordered a general retreat.

Mahan – The American left was thus routed, but Barney’s battery and its supporting infantry still held their ground. “During this period,” reported the Commodore,—that is, while his guns were being brought into battery, and the remainder of his seamen and marines posted to support them,—”the engagement continued, the enemy advancing, and our own army retreating before them, apparently in much disorder. At length the enemy made his appearance on the main road, in force, in front of my battery, and on seeing us made a halt. I reserved our fire. In a few minutes the enemy again advanced, when I ordered an 18-pounder to be fired, which completely cleared the road; shortly after, a second and a third attempt was made by the enemy to come forward, but all were destroyed. They then crossed into an open field and attempted to flank our right; he was met there by three 12-pounders, the marines under Captain Miller, and my men, acting as infantry, and again was totally cut up. By this time not a vestige of the American army remained, except a body of five or six hundred, posted on a height on my right, from whom I expected much support from their fine situation.” [377]

Mahan – In this expectation Barney was disappointed. The enemy desisted from direct attack and worked gradually round towards his right flank and rear. As they thus moved, the guns of course were turned towards them; but a charge being made up the hill by a force not exceeding half that of its defenders, they also “to my great mortification made no resistance, giving a fire or two, and retired. Our ammunition was expended, and unfortunately the drivers of my ammunition wagons had gone off in the general panic.” Barney himself, being wounded and unable to escape from loss of blood, was left a prisoner. Two of his officers were killed, and two wounded. The survivors stuck to him till he ordered them off the ground. Ross and Cockburn were brought to him, and greeted him with a marked respect and politeness; and he reported that, during the stay of the British in Bladensburg, he was treated by all “like a brother,” to use his own words. [378]

Mahan – The character of this affair is sufficiently shown by the above outline narrative, re-enforced by the account of the losses sustained. Of the victors sixty-four were killed, one hundred and eighty-five wounded. The defeated, by the estimate of their superintending surgeon, had ten or twelve killed and forty wounded. [379] Such a disparity of injury is usual when the defendants are behind fortifications; but in this case of an open field, and a river to be crossed by the assailants, the evident significance is that the party attacked did not wait to contest the ground, once the enemy had gained the bridge. After that, not only was the rout complete, but, save for Barney’s tenacity, there was almost no attempt at resistance. Ten pieces of cannon remained in the hands of the British. “The rapid flight of the enemy,” reported General Ross, “and his knowledge of the country, precluded the possibility of many prisoners being taken.” That night the British entered Washington.

Lossing – The Americans lost twenty-six killed and fifty-one wounded. The British loss was manifold greater. According to one of their officers who was in the battle, and yet living (Mr. Gleig, Chaplain General of the British Army), it was “upward of five hundred killed and wounded,” among them “several officers of rank and distinction.” The battle commenced at about noon, and ended at four o’clock.

Afterward

Gleig – This battle, by which the fate of the American capital was decided, began about one o’clock in the afternoon, and lasted till four. The loss on the part of the English was severe, since, out of two-thirds of the army, which were engaged, upwards of five hundred men were killed and wounded; and what rendered it doubly severe was, that among these were numbered several officers of rank and distinction. Colonel Thornton, who commanded the light brigade, Lieutenant-Colonel Wood, commanding the 85th regiment, and Major Brown, who led the advanced guard, were all severely wounded; and General Ross himself had a horse shot under him. On the side of the Americans the slaughter was not so great. Being in possession of a strong position, they were of course less exposed in defending, than the others in storming it; and had they conducted themselves with coolness and resolution, it is not conceivable how the battle could have been won. But the fact is, that, with the exception of a party of sailors from the gun-boats, under the command of Commodore Barney, no troops could behave worse than they did. The skirmishers were driven in as soon as attacked, the first line gave way without offering the slightest resistance, and the left of the main body was broken within half an hour after it was seriously engaged. Of the sailors, however, it would be injustice not to speak in the terms which their conduct merits. They were employed as gunners, and not only did they serve their guns with a quickness and precision which astonished their assailants, but they stood till some of them were actually bayoneted, with fuzes in their hands; nor was it till their leader was wounded and taken, and they saw themselves deserted on all sides by the soldiers, that they quitted the field. With respect to the British army, again, no line of distinction can be drawn. All did their duty, and none more gallantly than the rest; and though the brunt of the affair fell upon the light brigade, this was owing chiefly to the circumstance of its being at the head of the column, and perhaps also, in some degree, to its own rash impetuosity. The artillery, indeed, could do little; being unable to show itself in presence of a force so superior; but the six-pounder was nevertheless brought into action, and a corps of rockets proved of striking utility.

Mahan – The burning of Washington was the impressive culmination of the devastation to which the coast districts were everywhere exposed by the weakness of the country, while the battle of Bladensburg crowned the humiliation entailed upon the nation by the demagogic prejudices in favor of untrained patriotism, as supplying all defects for ordinary service in the field. In the defenders of Bladensburg was realized Jefferson’s ideal of a citizen soldiery, [382] unskilled, but strong in their love of home, flying to arms to oppose an invader; and they had every inspiring incentive to tenacity, for they, and they only, stood between the enemy and the centre and heart of national life. The position they occupied, though unfortified, had many natural advantages; while the enemy had to cross a river which, while in part fordable, was nevertheless an obstacle to rapid action, especially when confronted by the superior artillery the Americans had. The result has been told; but only when contrasted with the contemporary fight at Lundy’s Lane is Bladensburg rightly appreciated. Occurring precisely a month apart, and with men of the same race, they illustrate exactly the difference in military value between crude material and finished product.

Lossing – “It was not,” says one of Ross’s surviving aids, Sir Duncan M‘Dougall, in a letter to the author in 1861, “until he was warmly pressed that he consented to destroy the Capitol and President’s house, for the purpose of preventing a repetition of the uncivilized proceedings of the troops of the United States.” Fortunately for Ross’s sensibility there was a titled incendiary at hand in the person of Admiral Sir George Cockburn, who delighted in such inhuman work, and who literally became his torch-bearer.

Now see how I put all that together . . . or didn’t! Chapter 8 (Excerpt) – Battle of Bladensburg